Awakening to Injustice (1918-1940)

From an early age, Madeleine Parent became aware of social inequalities, first in her family, then in grade school and at university. Her educational path was an atypical one. By deciding to attend McGill University, she avoided the Catholic classic colleges that Francophones had to attend, at a time when a bachelor’s degree was a prerequisite for admission to the Université de Montréal or to Université Laval. University studies were a privilege of the elite, hence Madeleine’s early activism in favour of scholarships for the less affluent.

Her social conscience led to her interest in union action, particularly among the most exploited workers in the clothing and textile industries, where working conditions were exacerbated by the economic depression that still persisted in 1937, when the midinettes went on strike in Montréal.

Decisive Encounters and the Choice of Union Organization (1937- 1942)

While studying at McGill University, Madeleine Parent met Léa Roback, who had made a name for herself during the 1937 midinette strike, which had been organized by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU/UIOVD). Léa became an inspiration to Madeleine. Madeleine made her first forays into the union movement as the secretary of the organizing committee of the Conseil Fédéré des Métiers et du Travail de Montréal [Montréal Federated Council of Trades and Labour]. When the war broke out and the need for labour increased, women were recruited to work in heavy industry, munitions factories, and aircraft manufacturing, as well as in traditional industries. It was also a period of expansion for trade unionism. Madeleine soon began working as an organizer at Merchants Cotton and Dominion Textile. In 1942, she met Kent Rowley, a union organizer at an explosives factory and at the Montréal Cottons textile mill in Valleyfield.

Working Conditions and the Unionization of Women in the Textile Industry (1942-1946)

In 1943, Madeleine Parent began organizing textile workers at the Merchants cotton mill in Saint-Henri for the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA/OUTA), an industrial union.

The female workers were pleased by her presence. They were proud to participate in union meetings on equal footing with the men, and glad that attention was being paid to their specific working conditions, which included favouritism, discrimination, harassment, the arduousness of their tasks, the pace of the work, the issue of piecework, and the occasional presence of their children. Added to their load were their household responsibilities and motherhood. The union’s attention to their demands fostered a militant spirit and solidarity among them. These would prove essential in later negotiations and labour disputes.

Madeleine was also conscious of the discrimination suffered by Francophone workers, particularly at the Valleyfield factory, where managerial and superintendent positions were held by Anglophones.

Strikes at Dominion Textile: Montréal and Valleyfield (1946)

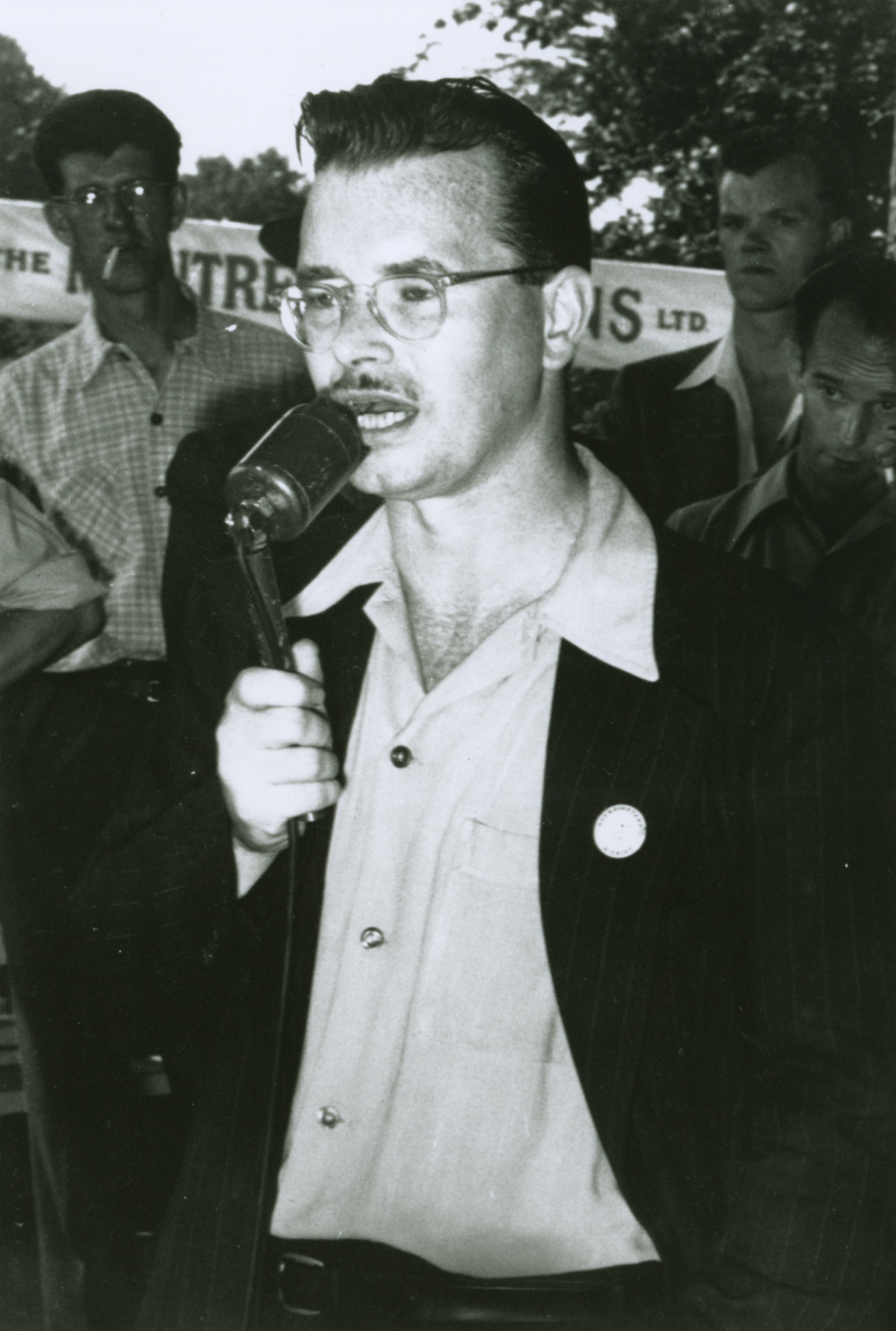

In 1946, when Canada was rocked by the biggest upsurge in labour unrest since the great strikes of 1919, Kent Rowley, organizer of the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA/OUTA), and Madeleine Parent led strikes at Dominion Textile’s Valleyfield and Montréal mills. At the time, Dominion Textile dominated the textile industry, which employed the highest proportion of women in Quebec, who were traditionally known as docile, exploitable workers.

Opposition from the company, which was determined to decertify the union, was compounded by the hostile, intensely anti-union political power embodied by Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale government. For one hundred days, the struggle for Local 100 union certification and improved working conditions was marked by efforts by clergy members to discredit the strikers and the union organizers, police action on behalf of the company and of the scab workers, harassment by the company, and accusations of communism levelled at the organizers. Madeleine and Kent were arrested and put on trial.

The Cold War directly affected the labour movement, in that social demands and labour activism became suspect and were often branded as communist. The strike in Valleyfield, which was largely supported by the public, ended in victory for the workers, with recognition of the union and the signing of a collective agreement. At the age of 28, Madeleine became a heroine among the textile workers.

The Strike at Ayers Woolen Mills in Lachute (1946-1947)

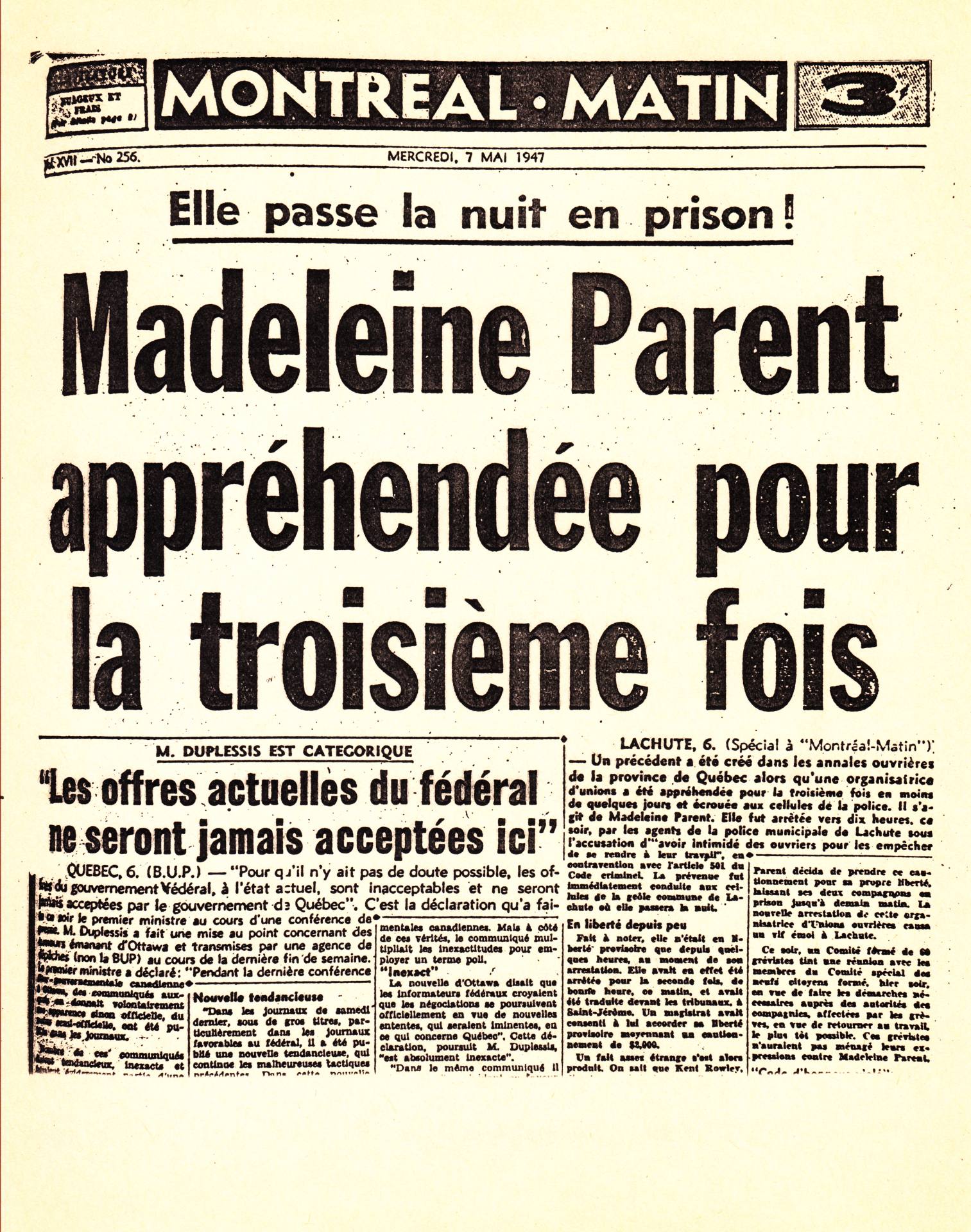

In response to an appeal from workers at the Ayers Woolen Mills in Lachute, Madeleine began organizing a strike in April 1947. The demands included wage increases and improved working conditions. Approximately six hundred workers took part in the lengthy labour dispute, which was marked by inter-union rivalries and raiding between the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA/OUTA), which was Madeleine and Kent’s union, and the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA/UOTA); heavy police repression; and the pervasive anti-communist climate of post-war America.

Madeleine Parent, Kent Rowley, and union organizer Azélus Beaucage were arrested more than once on charges of obstructing the police, inciting a strike, and illegal picketing, as well as on the much more serious charge of seditious conspiracy. Although the strike was not successful, it is remembered for Madeleine’s trial for sedition.

The Trial for Seditious Conspiracy (1947-1955)

Against the backdrop of the Cold War and the fiercely anti-communist sentiment it engendered, as well as the anti-union stance of Quebec’s ruling Union Nationale political party, the longest trial in the province’s legal history began. During Madeleine Parent’s trial for seditious conspiracy (against the government?) and the intimidation of Ayers company employees, prosecutors called several witnesses in an attempt to associate her and Kent Rowley with the communist movement, even though the Communist Party of Canada had very few members in Quebec.

The trial began in Saint-Jérôme in 1947. After she was convicted, Madeleine filed an appeal, but since the first trial had been quashed, the Court of Appeal ordered another trial, which was delayed from year to year until Madeleine’s acquittal in 1955.

Women’s Work and the Place of Women in Quebec’s Unions (1940s and 1950s)

Despite wartime gains in wages and working conditions, once the war ended, the rising cost of living, the sexual division of labour, and wage inequalities particularly affected female workers.

Madeleine Parent’s keen awareness of pay inequities led her to call for equal pay for equal work. Later, in line with the position of the International Labour Organization, she demanded equal pay for work of equal value, in other words, pay equity.

Madeleine’s career reflected the changing status of women in unions. She was the first woman to sit on the executive committee of the Montréal Trades and Labour Council, and she went on to co-found the Confederation of Canadian Unions.

Kent Rowley (1942-1978)

When Madeleine first met Kent Rowley, who was the Canadian director of the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA/OUTA), in 1942, she was married to union organizer Val Bjarnason. Until the 1960s, only the Canadian Senate could grant a divorce in Quebec, and Catholics who could afford it had their marriages annulled by the Church in Rome. After the war, Madeleine and Val mutually agreed to divorce, but to avoid a scandal during union negotiations, they delayed the proceedings until 1952.

Madeleine and Kent Rowley married in 1953. They shared the same ideals, the same passion for their work, and the same approaches to labour organization. Together, they created the Confederation of Canadian Unions. Their marriage was a happy one until 1978, when Kent died of a heart attack.

Confrontation with the International Union (1949-1952)

Accusations of communist allegiance against Madeleine Parent were made not only by the Catholic clergy and the political authorities, but also by the international trade unions. During the Cold War, trade unions, like social democratic and socialist organizations, feared being accused of communist sympathies more than anything else. International unions, such as the United Textile Workers of America, distanced themselves from unions and organizers who were suspected of being communist. The second Dominion Textile strike in Valleyfield in 1952 provided the UTWA/OUTA with an excuse to expel Madeleine Parent and Kent Rowley from the union.

Duplessis (1944-1959)

Madeleine Parent was the undisputed nemesis of Premier Maurice Duplessis. As a populist conservative, a Catholic, and a defender of traditional values, the Premier favoured paternalism in labour relations. Retroactive labour laws reflected his distrust of unions and his fear of communists. During his last two terms in office, opposition grew in the unions, as well as in cultural and political circles. By the time of his sudden death in 1959, the Liberals were ready to take over and usher in an era of reform, which soon came to be known as the Quiet Revolution.

The October Crisis in Quebec (1970)

The War Measures Act, which was invoked on October 16, 1970, to defeat the Front de Libération du Québec, was not without its effects on Madeleine Parent and Kent Rowley. Although they had been living in Ontario together since 1967, their home in Montréal was raided several times by the police.

The Confederation of Canadian Unions (1952-1969)

In 1954, following their expulsion from the international union, Madeleine Parent and Kent Rowley founded the Canadian Textile Council (CTC), a Canadian trade union movement that was independent of the U.S. central labour bodies, less bureaucratic, and closer to the rank and file. Kent moved to Ontario in 1952, at the end of the Dominion Textile strike, and continued his organizing work within the CTC, which later became the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union (CTCU), while Madeleine pursued what she called “rearguard action” in Quebec. In 1956, an initial victory at the Harding Carpet Factory in Brantford proved crucial for Canadian unionism.

Madeleine moved to Brantford in 1967 to live with Kent. In July 1969 in Sudbury, the couple founded the Confederation of Canadian Unions (CCU), which brought together independent unions in the textile, pulp and paper, and construction industries from several provinces. Kent was secretary-treasurer and Madeleine sat on the executive as a representative of the CTCU. The climate was favourable to union nationalism, as the Canadian left, embodied by the Waffle movement in the left wing of the New Democratic Party, was fighting the American stranglehold on both unions and the economy. These progressive nationalists supported the strikes led by the CTCU at the Texpack plant in Brantford in 1971 and at Artistic Woodwork in Toronto in 1973. For Madeleine Parent, the 1970s marked a commitment to Canadian unionism, particularly among female immigrant workers.

Strikes in the Ontario Manufacturing Industry (1971-1973)

Three strikes in Ontario showcased Madeleine’s talents as an organizer. The first, at the American Hospital Supply Company’s Texpack plant near Brantford in 1971, mobilized an immigrant workforce and ended in victory for the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union.

The second, at Artistic Woodwork in Toronto in 1973, ended in victory after three months, but the victory was short-lived, as the union was unable to gain a foothold. However, the strike received strong popular support and once again succeeded in reaching immigrant workers.

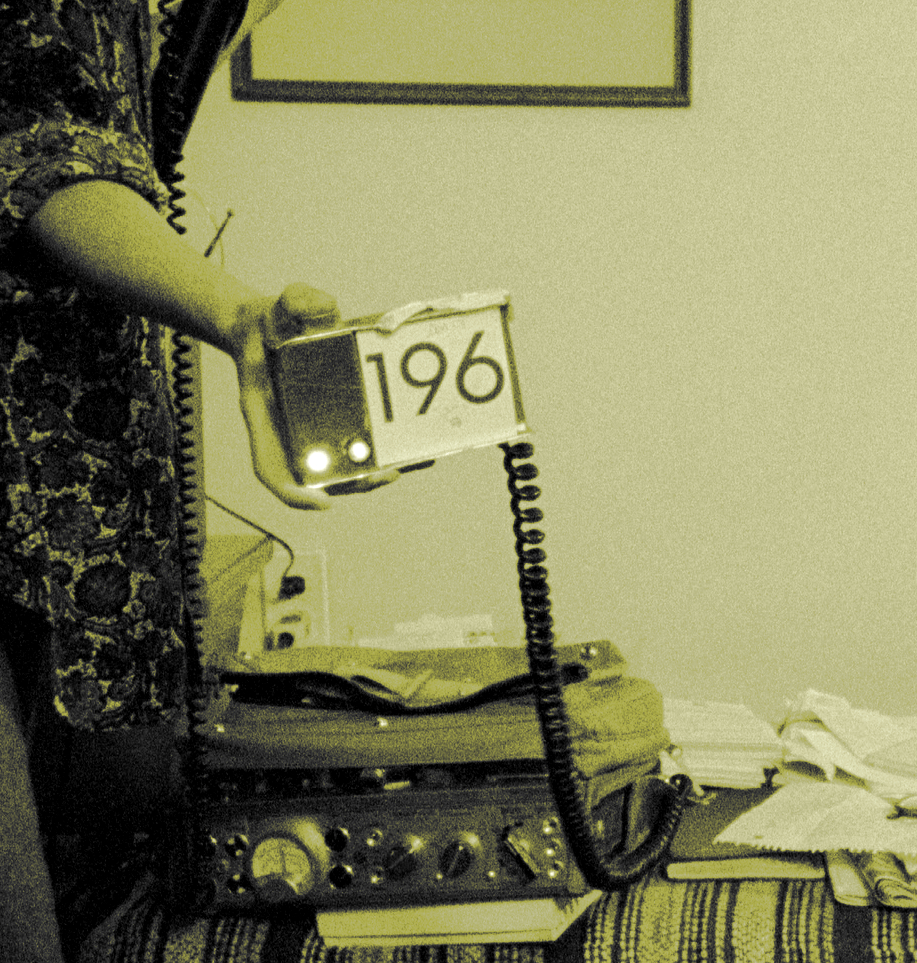

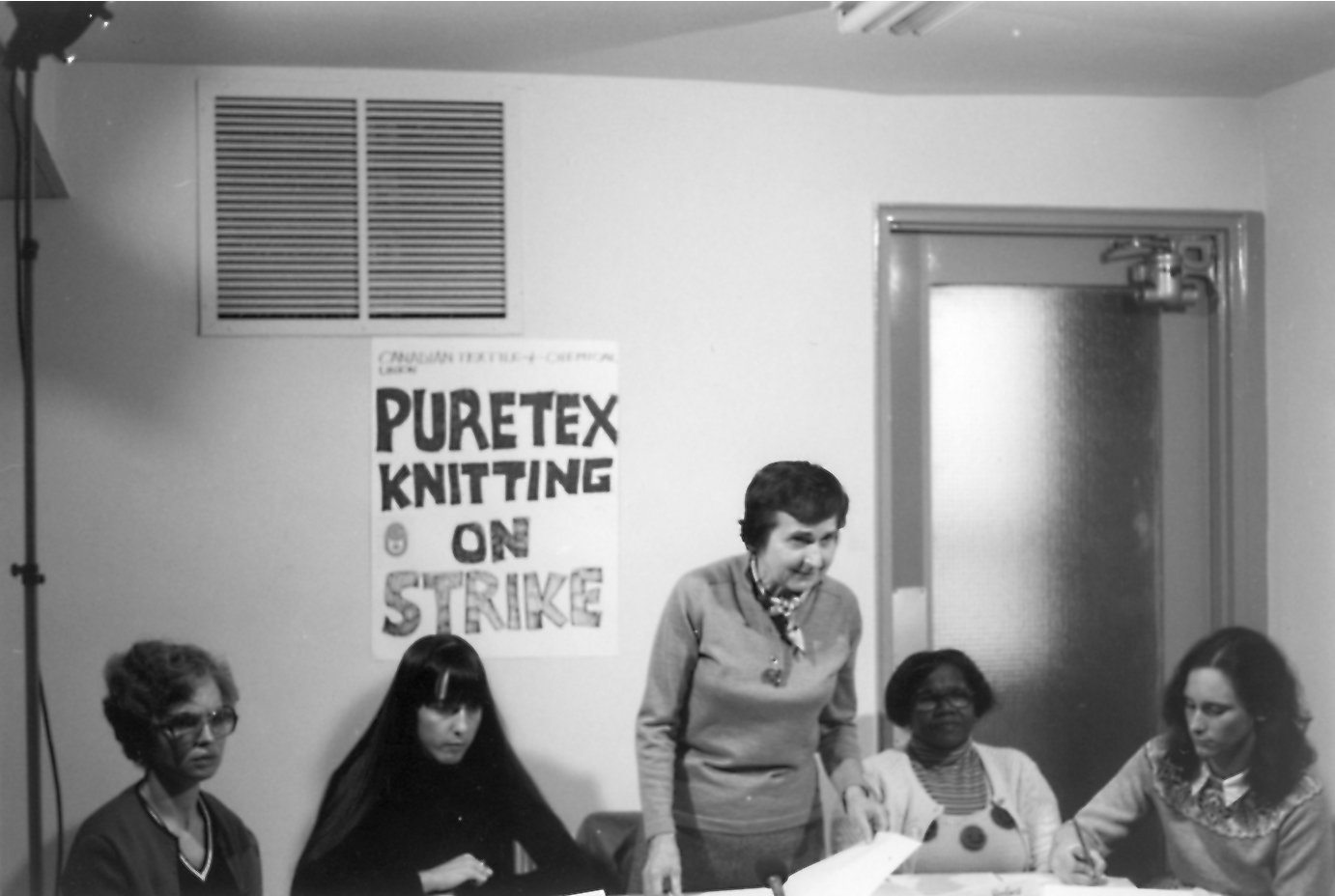

The third, at the Puretex factory in 1976, is discussed later on this page in the section entitled “Women in the Unions” (video clip: The Strike at Puretex Knitting and Surveillance Cameras). The strike, which fought the installation of surveillance cameras in particular, lasted three months and ended in victory for the immigrant women workers.

These strikes brought to light the hostility of the international unions, police brutality, the involvement of scab workers, the support of progressive elements outside the labour movement (students, feminists, the NDP’s Waffle group), and the political and nationalist aspects of the union struggles led by Madeleine Parent.

Women in the Unions (1940s to 1970s)

From the very start of her career as a union organizer, Madeleine Parent attached particular importance to the working conditions of female workers. When she moved to Ontario in 1967, she continued her work with Italian, Greek, Chinese, Portuguese, and African-Canadian immigrant women. These workers were promoted to positions of responsibility in the locals of the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union, and the meetings offered translation into their own languages.

Madeleine, who was sensitive to the unique conditions of working women, demanded maternity leave with recognition of seniority from the start of employment. One strike in particular—at the Puretex garment factory in Toronto in 1978, against the installation of surveillance cameras—exemplified Madeleine’s work with immigrant women workers. The three-month strike, which proved very popular with the workers, ended in victory for the immigrant workers.

The Emergence of the Independent Women’s Movement in Canada (1970-1973)

During the 1970s, Madeleine Parent increasingly identified with the feminist movement. A coalition of women’s groups in Canada, led by Laura Sabia, worked within the Committee for the Equality of Women in Canada to obtain a Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada (the Bird Commission). Following the tabling of the Commission’s report in December 1970, Madeleine took an active part in a meeting called by the coalition to discuss the Commission’s recommendations. At the conference in 1972, entitled “Strategy for Change,” she supported the creation of a coalition of independent feminist groups, i.e. with no ties to the government. This was the founding of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC). She ensured women workers were represented and she campaigned to make pay equity a priority. She was also an ally to Indigenous women who were defending their rights on reserves on the same basis as men.

Support for Indigenous Women (1970s to 1990s)

Since 1869, the Indian Act had stripped Indian status from women who married non-Indian men, as well as from their children. Thanks to the efforts of Mary Two-Axe Earley and Indian Rights for Indian Women, the Bird Commission recommended a change in the law to end discrimination against married Indigenous women. Madeleine Parent and the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC) joined the fight of Indigenous women and, in 1985, Bill C31 amended the Indian Act to end discrimination in accordance with Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights.

In 1984, when federal public servant Mary Pitawanakwat was the victim of harassment and discrimination in Saskatchewan, she took her case to the Canadian Human Rights Commission with the support of the NAC, particularly the Native Women’s Support Committee, on which Madeleine Parent sat. Her battle lasted several years and ended in victory in 1991. Madeleine’s support turned into friendship throughout Mary’s illness, which took her life shortly after she returned to work.

Madeleine, inspired by her first encounters with Indigenous people as a child, never stopped speaking out and taking action against prejudice, discrimination, and acts of racism in any form.

An Active, Engaged Retirement (1983-1999)

This interview with Madeleine Parent took place in 1999, in a time of economic liberalism and austerity, under the PQ government of Lucien Bouchard. Deeply involved in political and economic debates, she bridged the gaps between grassroots and labour movements, between Francophone and Anglophone groups, and between generations. In the years following her retirement, she was active with the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, Solidarité Populaire Québec, the Fédération des Femmes du Québec, and the World March of Women. The causes she defended included pay equity, the abolition of “orphan clauses” in collective agreements, the defence of human rights, alterglobalization, and access to abortion.

Secrets of an Activist

Madeleine described the principles that guided her life as an activist, notably the importance of listening to workers and staying calm during negotiations and confrontations, to Françoise David, who was then president of the Fédération des Femmes du Québec. She also described her lifelong passion for fighting exploitation and raising awareness, as well as the importance of solidarity and her hopes for a better future.