A Jewish Seniors’ Residence Founded by her Grandmother (1910s or 1920s)

At the beginning of the 20th century, Montréal’s Jewish community was growing rapidly. It therefore sought to create institutions of all kinds to meet its many social and cultural needs. There was a particular need to help the most vulnerable members of society, such as destitute elderly women who were on their own. Léa’s grandparents, notably her grandmother Sarah Steinhouse, contributed to this movement by founding a seniors’ residence, which later became the Donald Berman Maimonides Geriatric Centre. The first residence was established on Evans Street in 1910. In 1923, a second location was opened on Hôtel-de-Ville Street under the name “B. & S. Steinhouse Old People’s Home.”

Joining the Communist Party in Berlin (1932)

While Léa was living in Germany, the country was hit by the economic crisis of 1929, which quickly turned into a political crisis, as the many existing parties, both left-wing and right-wing, were unable to form stable governments. The Communist Party sought to combat unemployment and social inequality, which is why Léa chose to join.

But its members were increasingly closely monitored and documented, as she put it (everyone was in the map room). The rise of Nazism heralded even darker days. After Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in November 1932, he called for new elections in February 1933 and set about banning socialist and communist parties and newspapers, imprisoning their leaders and supporters, and ostracizing Jews. Léa therefore decided to return to Canada.

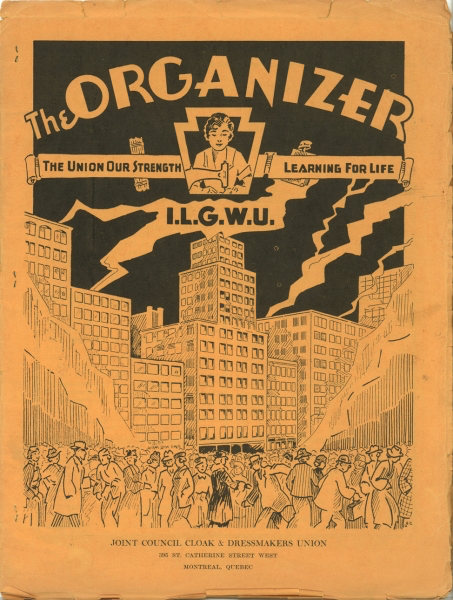

The Unionization of Montréal’s Dressmakers (1936-1937)

In the following clips, Léa talks about her role in organizing Montréal’s dressmakers, also known as midinettes; their working conditions in the 1930s; their grievances; and the strike they called in 1937 under the banner of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union/Union Internationale des Ouvriers du Vêtement pour Dames (ILGWU/UIOVD), which represented them. The midinettes overcame the ethnic and linguistic barriers that divided them, thanks in part to Léa, and showed great solidarity during the strike, which ended in their favour.

A Union Organizer in the Dressmaking Industry (1936)

In 1936, Léa was working at the communist bookshop Modern Bookstore when she was asked by Ted Allan, a young communist journalist who would go on to become a playwright and screenwriter, to work as an “educational director” for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU/UIOVD). Alongside Rose Pesotta, Léa helped unionize the garment factories that were home to the dressmaking industry.

Pesotta, of whom Léa spoke with great admiration, was one of the most influential activists of the 20th century. An anarchist and a feminist, became a union organizer in the garment sector in the 1930s on behalf of the ILGWU/UIOVD. She travelled to Montréal in September 1936 to lead the midinette unionization campaign, which was then underway. Léa further discusses Pesotta in the clip entitled “The Life of a Union Activist: Rose Pesotta and Léa Roback” (further down this page). Rose Pesotta became vice-president of the ILGWU/UIOVD, but eventually resigned due to the sexism of the male leaders.

As for Yvette Charpentier, she joined the international union thanks to Rose Pesotta. She was very active in the 1937 strike, and later established herself as a key union organizer during World War II.

Working Conditions in the Dressmaking Industry (1936)

In 1936, Montreal’s dressmaking industry, which at the time was the hub of Canada’s garment industry, was comprised of over a hundred workshops that were concentrated along The Main (Saint-Laurent Street) and in the area of De Bleury and Sainte-Catherine Streets. The workshops employed workers of diverse ethnic and linguistic origins, the majority of whom were women.

The Midinette Ball, which was organized by the ILGWU/UIOVD from 1938 onwards and criticized by Léa Roback, was an annual event attended not only by female workers, but also by businessmen and politicians and their wives. From 1948 onward, it included a beauty contest for female workers. The event ceased to be held in the 1980s.

Women’s Grievances in the Dressmaking Industry (1936)

The dressmakers’ grievances were many, especially when it came to the sexual harassment to which they were subjected and which they called favouritism, or “groping.” Those who consented to being touched or to performing other sexual favours obtained more pieces of fabric to sew, or pieces that were easier to assemble. These were definite advantages in a piecework industry, where speed of execution was paramount to increasing their wages. Also, women who were related to each other often recorded their working hours at the factory on the same timecard, thus saving the boss a wage. This is what Léa refers to when she says, “two on the same card.”

A pinker is a worker who operates a sewing machine designed to finish the edges of the fabric and prevent fraying.

Within the union itself, tensions were high, notably between Léa and other activists on the one hand, and the union leadership on the other, namely Bernard Shane, who was then the ILGWU/UIOVD’s agent in Canada, where he had already organized the tailors, and David Dubinsky, the union’s international president from 1932 to 1966. These problems were exacerbated by competition from the Ligue Catholique des Ouvriers de l’Aiguille [Catholic Needleworkers’ League], a union affiliated with the Canadian Confederation of Catholic Workers (CCCW).

Strike in the Dressmaking Industry (1937)

On April 15, 1937, as the economic crisis continued to rage, five thousand female dressmakers launched a strike that profoundly marked the history of unionism in Quebec. By the time they returned to work on May 3 after a three-week walkout, they had secured their first labour contract with the 80 employer members of the Dress Manufacturers’ Guild. It included union recognition, a 44-hour work week, and a substantial wage increase from $11 to $16 a week.

In this clip, Léa mentions “le bon boss” [the good boss], no doubt referring to Yvon Deschamps’ famous monologue Les unions, qu’ossa donne? [What good are unions?].

Tensions in the ILGWU/UIOVD Union (1937-1939)

After the victory of 1937, differences of opinion within the ILGWU/UIOVD leadership intensified. Certain leaders with ties to the Communist Party, such as Léa, wished to maintain a firm stance, while others preferred to be more friendly with the employers, at the risk of weakening the position of the female workers. These tensions ultimately prompted Léa to resign from her position.

Claude Jodoin, one of the moderates, served as representative and negotiator for the ILGWU/UIOVD during the1937 strike. He later became the union’s Canadian director, as well as vice-president of the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada.

Racism in the Dressmaking Industry (1937-1939)

Léa addresses the racism experienced by a worker of African descent at the hands of an employer in the dressmaking industry. Like anti-Semitism, racism intensified during the economic crisis of the 1930s, as social tensions increased. The woman in question was a draper. Drapers are responsible for finishing the garments and checking the work of others.

The Life of a Union Activist: Rose Pesotta and Léa Roback (1930s)

This clip refers to the fire that ravaged the Triangle Shirtwaist garment factory in New York City on March 25, 1911, killing 146 workers, most of whom were young immigrant women. Léa then discusses the difficulties of being a female activist in a male-dominated, sexist environment, a choice that is difficult to balance with family responsibilities, and can result in loneliness. Although she herself had a supportive family, Léa cites the example of Rose Pesotta, who came to Montréal alone, with no knowledge of French, to organize the female garment workers. She referred to this higher up on this page, in the clip entitled “A Union Organizer in the Dressmaking Industry.”

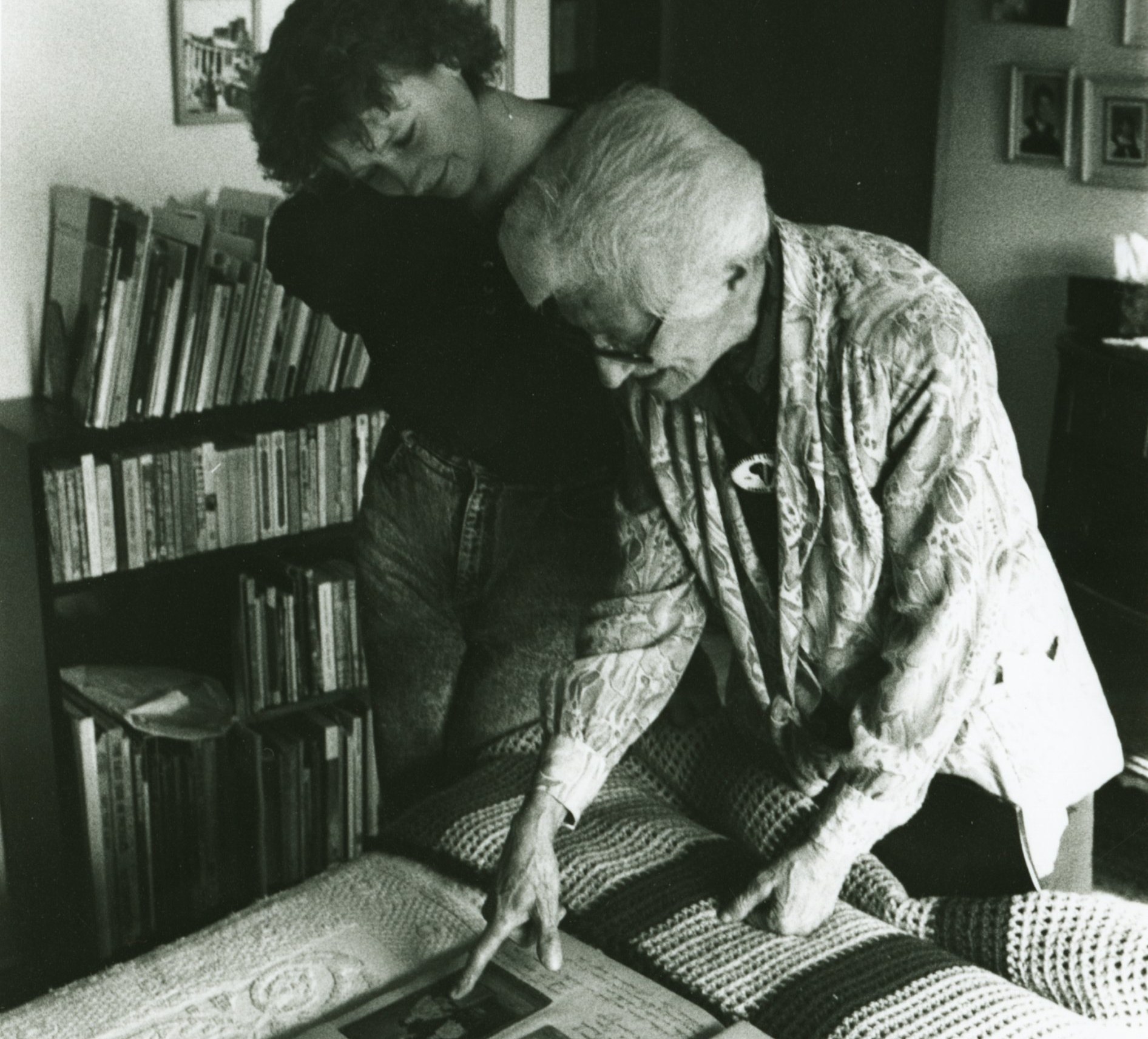

Léa also mentions Madeleine Parent, who headed the United Textile Workers of America/Ouvriers Unis des Textiles d’Amérique (UTWA/OUTA) with her husband Kent Rowley from 1942 to 1952. For more information, see the film Madeleine Parent, Tisserande de solidarités and the archival file about Madeleine Parent.

Unwanted Pregnancies: The Miséricorde Hospital and Clandestine Abortions (1930s and 1940s)

Léa provided help to pregnant single female workers who either wished to bring their pregnancies to term and give birth or get an abortion. She also promoted the use of contraception by married couples.

Until the 1960s, non-marital pregnancies were strongly condemned by society, while the Criminal Code of Canada prohibited the distribution of contraceptive information or items, as well as the practice of abortion. In these circumstances, young unmarried French-Canadians who became pregnant essentially had two choices: to give birth in absolute secrecy at the Miséricorde Hospital, an establishment run by an order of nuns of the same name, or to seek clandestine abortions, either by untrained abortionists or by doctors willing to perform the illegal procedure at the risk of prosecution, like certain Jewish doctors Léa was familiar with. Most of the babies born at La Miséricorde were subsequently placed in nurseries, waiting to either be taken back by their mothers or put up for adoption, but a staggering number of them died from a lack of adequate care.

The nurse Léa refers to regarding contraception may be Dorothea Palmer, a social worker who worked in Eastview (now Vanier, a suburb of Ottawa) during the Depression, distributing information on contraception. Palmer was arrested for breaking the law, but was acquitted in a 1936 trial.

Women’s Work and Domestic Service (1939-1945)

During World War II, many women, particularly married women, found jobs in war factories. With so many men away fighting in the war, there was a shortage of labour, and some women were even assigned to so-called “masculine” tasks. When peace was restored and the wartime factories closed, this unprecedented situation came to an end, but the development of the service industry allowed women, and young girls in particular, to work as office clerks and saleswomen, and to continue to avoid working as maids. Since then, they have increasingly been replaced by immigrant women.

Unionization at RCA Victor in the Neighbourhood of Saint-Henri (1941)

By creating a labour shortage, World War II greatly favoured the unionization of workers; this is what Léa refers to when she says, “It was time.” Capitalizing on the situation, the Communist Party sent activists like Léa Roback and Bob Haddow, a member of the International Association of Machinists, into the war factories to unionize them. At that time, there were many factories and thousands of workers in the neighbourhood of Saint-Henri, making it an important centre for union campaigns.

“Time studies,” as Léa called them, which set the pace of the machines in order to maximize production, were one of the elements of their working conditions that the workers were opposed to.

In 1943, the RCA Victor workers that Léa helped organize joined the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, an American union that was affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Three years later, with Léa’s help, the workers decided to join the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), a union affiliated with the AFL’s competitor, the more aggressive Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO). In 1950, however, the UE became a victim of the anti-communist struggle and was expelled from the CIO.

Poverty in the Neighbourhood of Saint-Henri (1930s and 1940s)

Located on the banks of the Lachine Canal, where numerous factories were built from the 19th century onward, the Saint-Henri district was home to one of Canada’s poorest working-class populations. The living conditions of its inhabitants during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s were immortalized in Gabrielle Roy’s 1945 novel The Tin Flute, as well as in Hubert Aquin’s 1962 film À Saint-Henri le 5 septembre.

Women in a Men’s World (1940s)

In this clip, Léa discusses the rampant sexism experienced by female workers at the hands of their employers, and which she herself experienced in the union, where women were in the minority. For a very long time, the demands of female workers and the problems they experienced in the workplace were ignored or treated in a cavalier manner. For example, most collective agreements did not include maternity leave clauses, and they set lower pay scales for women than for men, a situation that only began to change in the 1970s.

Léa also refers to Huguette Plamondon, a union activist who rose through the ranks to become the first female vice-president of the Canadian Labour Congress in 1956.

Anti-Communist Purges in the Unions (1940s and 1950s)

During the Cold War (1945-1989), Western political leaders condemned the communist regime in Moscow, as well as those who supported it. In North America, the fight against communism became a veritable witch hunt when, in the early 1950s, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy chaired a commission aimed at tracking down possible communist agents and reporting, charging, and convicting them.

“McCarthyism,” which became synonymous with the anti-communist struggle, soon raged within American unions, many of which had branches in Canada and Quebec, such as the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), where Léa worked. Union members suspected of communist sympathies were either ousted from their positions and replaced by less extreme leaders, or their union’s certification was simply revoked, rendering their activities virtually illegal. As for the rank-and-file activists, they were fired from their jobs and blocklisted so that they could never again find work in their fields. In Quebec, Maurice Duplessis’ government also applied the “Padlock Law,” which had been adopted in the 1930s, to prevent unions from meeting.

An Activist in Search of Employment (1950s and 1960s)

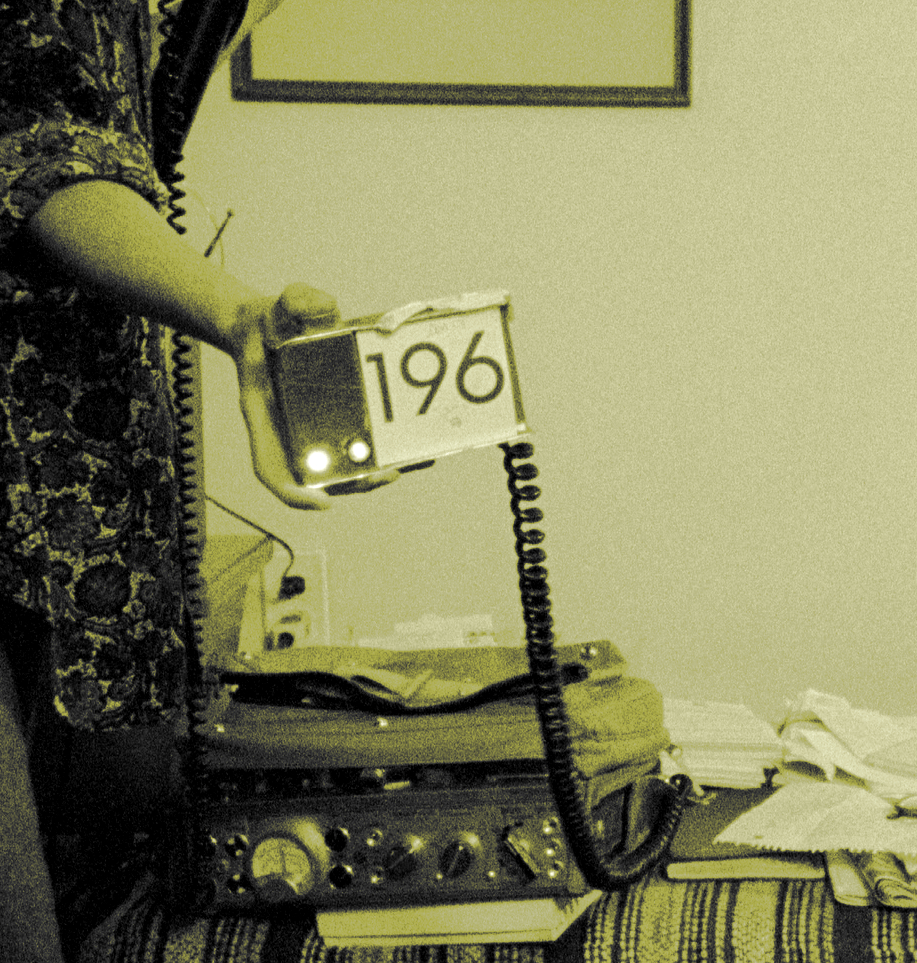

In this clip, Léa describes some of the employment positions she held after she quit the union movement. Her communist background and dissenting views made it difficult for her to find work. This experience was shared by many other activists who were accused of being communists in Quebec in the 1950s and 1960s. She also describes the repeated searches for “subversive” literature that were carried out by the police at her mother’s home, under the terms of the Padlock Law, which was declared unconstitutional in 1957.

The Split with the Communist Party (1950s)

Léa attributes her resignation from the Communist Party to its lack of recognition of Francophones and to their status in the Party as a minority group, all across Canada. Her departure came after Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, published a report in 1956 revealing the abuses committed by the regime of Joseph Stalin, who had died three years earlier. The disclosure of these abuses led to the defection of a number of communist activists throughout the Western world.